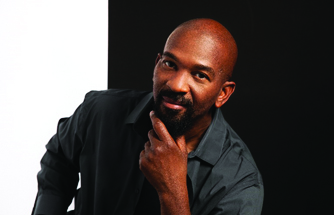

BY DR. REBEKAH MCCLOUD, GUEST WRITER TO THE TIMES

OCALA — Mixed-media artist, award winner, author, and former art teacher are but a few of the ways to describe Charles Eady. A native of Fairfax, South Carolina, a small town Eady remembers as having one stop light, he cannot recall a time when art was not a part of his life. “I would always draw and paint. My oldest brother could draw. When he gave me the nod to draw, it was on. I also had a supportive aunt. When I went back home as an adult, people asked me if I still drew. I had a classmate come to the Appleton Museum to see my exhibit. She asked if I thought all of the drawings I did back then would lead to this. I didn’t, I just loved art.”

Eady attended Claflin University. He began as an art major but earned a BA in Art Education. Even though Claflin is an HBCU, Eady said none of his professors taught about Black artists. “A print-making instructor (Mr. Ellison) would mention things along the way. He took a group of us to Atlanta and there was an exhibit at one of the museums. That is where I saw my first Black artist, Jacob Lawrence. On the trip, my instructor sold a piece of his art. That encouraged me.”

After college graduation, Eady moved to Florida and taught art for 24 years at all grade levels. He was impressed by the students’ artwork and spent over half of his career as a high school art teacher. While Eady was passionate about teaching art, he ran into roadblocks. “I was discouraged from telling the truth about art and artists. I thought schools would be open to allowing students to learn about the diversity of art and artists. Not so much. Once I had a student who was writing a paper and she asked me about artists. I started giving her the names of traditional, white artists. I told myself to wait; this is what happened to me. So, I stopped and started to give her the names of Black artists like Jacob Lawrence and Jean-Michel Basquiat.” After that, Eady became more aware of the importance of Black history.

He began researching Black history, especially in the South. “I found a way beyond what I thought I would find. Historians would leave out information, twist, or change it to match the narrative that is being said.” He decided the truth had to be told and the book, Hidden Freedom: The South Before Racism, was born. “I tried to find someone to write the book. I kept being told to write it myself. When I started to write, it was as if the characters had been waiting. The research changed my perspective of Blacks in the south. I learned about free Blacks, who could read, write, move freely, owned property, had money, and were business owners. The America that we know now, was structured after the Civil War when during Reconstruction, racism became an institution itself. Racism is there, but in anonymity,” he said.

To compliment his research and accommodate the truth, Eady started painting. “The artwork had a conversation with me. When I first started, the paintings wanted to be bigger. Once I made them bigger, I felt a release. It felt like this was the true thing they wanted to be.” He included copies of legal documents he found in his paintings. He said he wanted to provide “a visualization of the truth via an eye witness account of the documents. The mere presence of the documents shows the truth.” Most pieces, done in oils and acrylics, include a collage or silkscreen and range in size from 48X76 to 70X84.

“Art can open windows of history. It can release a greater understanding of events with visual evidence. Sometimes we just need to see it for ourselves, so I paint for others to see eyewitness accounts in the telling of Blacks in history,” Eady concluded.

Eady was recently featured in a solo exhibit at the Appleton Museum of Art (Ocala, FL). One of his paintings, American Jockey, is in the museum’s permanent collection. His art has been displayed across the nation. He has several exhibits scheduled for 2025, including one at the Hannibal Square Heritage Center and the Crealde School of Art, both in Winter Park.